The mystery behind an iconic photograph of Washington, D.C., in the 1970s leads back to Carleton

In the early morning of July 19, 1974, Jan Harley ’68 was awakened by friends at her Washington, D.C., home and presented with her high-school prom dress. “Put this on,” she was told. Limousines waited outside. Her boyfriend was in a horse-drawn carriage.

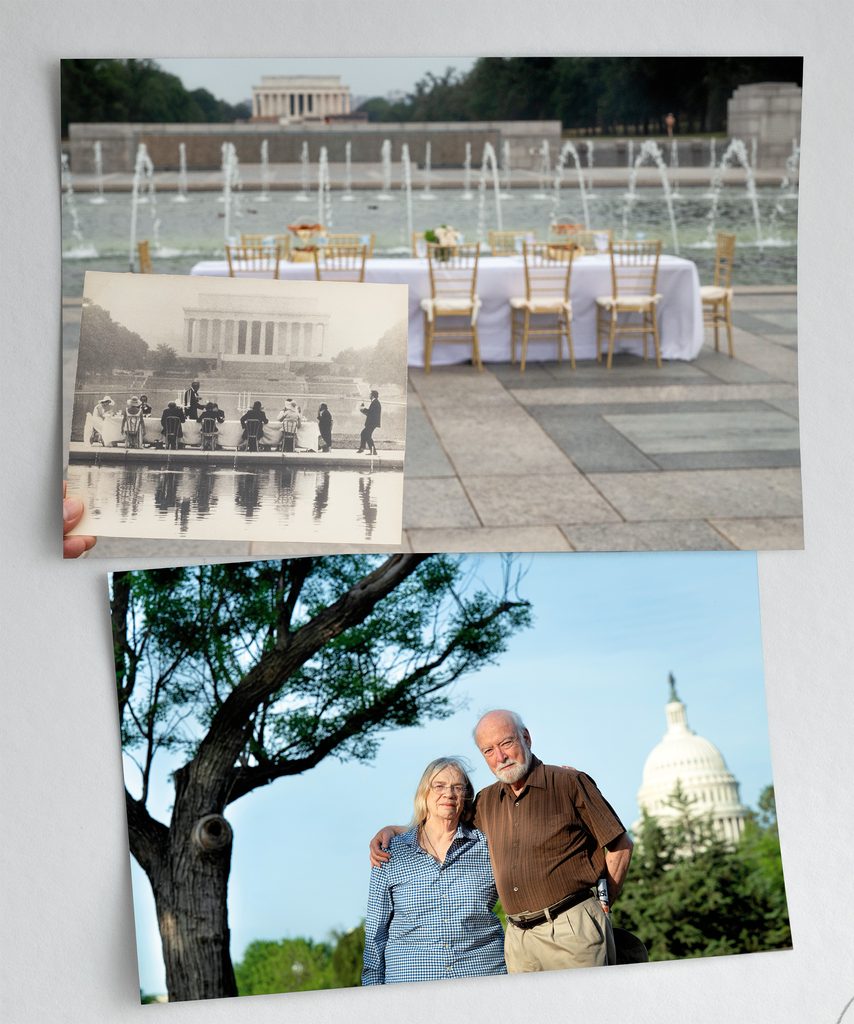

No one would tell her where they were going. But as the sun came up behind the Capitol, the caravan arrived at the National Mall. Most of the men were dressed in old-fashioned ties and tails, the women in hats and gowns. A table beside the Reflecting Pool was set for 12, with smoked salmon and champagne. A string quartet played nearby. A guest in military dress sliced pastries with his sword.

It was Harley’s 28th birthday. “We decided it had to be the most over-the-top event,” recalls one of the organizers, “the most bizarre we had ever pulled off.”

The Washington Post sent a photographer. Soon, a picture of these apparently carefree youth, breakfasting by the Lincoln Memorial, appeared in newspapers around the country. It was curious and decadent—like the ’70s themselves—and went on to become one of the Post’s best-loved images of the decade. It’s still among the best-selling prints from the paper’s archives.

Yet almost nothing was known about the people in the picture until just last year, when the Post invited them back for a 50th reunion. Most of them, no surprise, worked in government. Many were Carls—right down to the string quartet.

In fact, by the early 1970s, there were so many recent Carleton graduates in the nation’s capital that a trip to the Hill would almost guarantee an encounter. “It was an exciting time,” as one alum put it, “to be a Carl in Washington.”

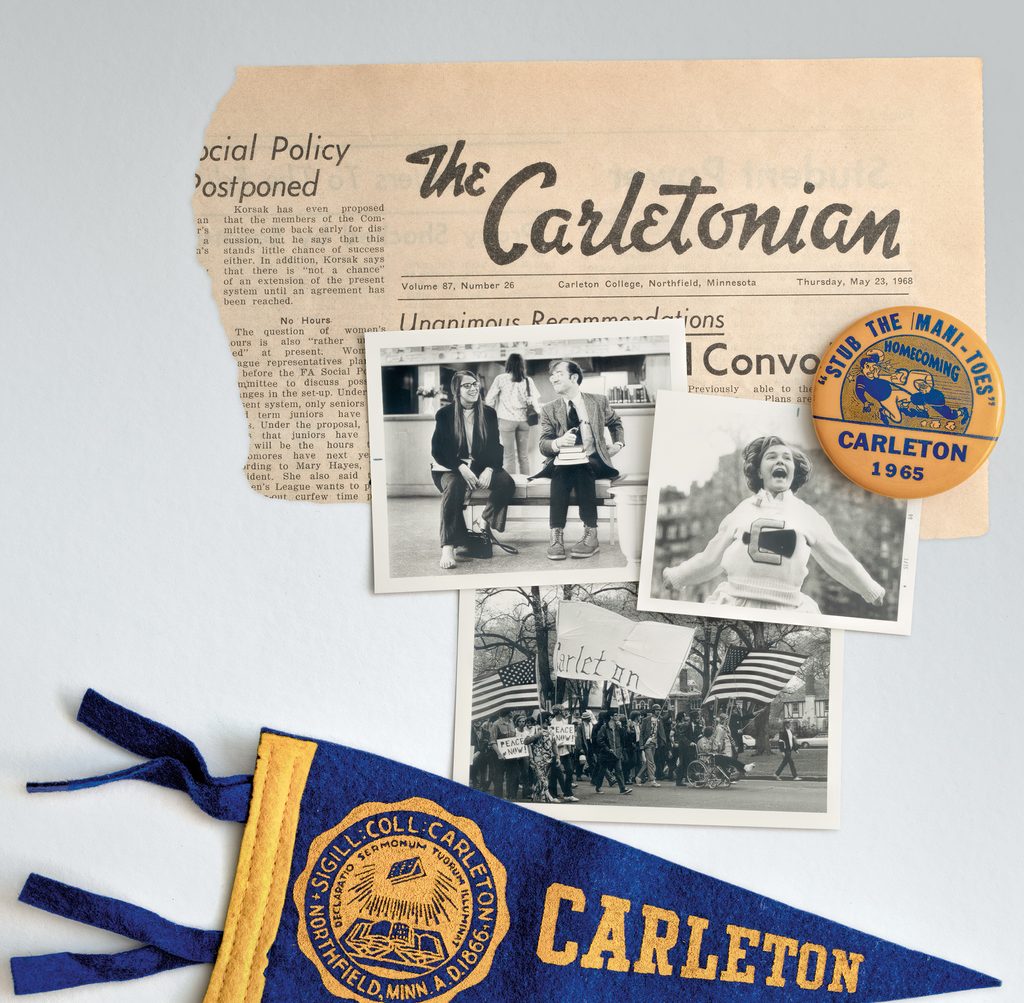

Harley came to Carleton in the fall of 1964, from Cleveland, and moved into a quad in Nourse Hall. The nunnery, as it was sometimes called. Women only.

“It was not a party campus,” recalls Barb Windschill Sommer ’68, one of Harley’s three roommates along with Cay Buser ’68 and Tobi Hanna-Davies ’68. Sommer had gone to high school about three hours away in Worthington, where the culture revolved around boys’ sports. Carleton seemed an oasis. Buser had grown up in St. Paul, the only child of a father who had attended Carleton during World War II—not as a student but as part of a U.S. Army program, which trained German speakers to drop behind the lines and aid the resistance. (The war ended before he could deploy.) Roommates were a revelation. “All of a sudden, I had three people my own age with similar interests,” Buser says. “We immediately formed a bond.”

Campus life was divided—men on the west side, women on the east—if not equally. Women had curfews. Men did not. Women had to wear skirts or dresses unless the temperature dropped below 10 degrees. Men could wear almost anything (except skirts or dresses).

Little had changed since the 1940s. There were freshman beanies and bonfires, Sunday convocations and white-tablecloth dinners. “It was in loco parentis, the college in the role of the parent,” says Carleton archivist Eric Hillemann.

Larry Gould, the Antarctic explorer turned scholar who had overseen Carleton’s rise to prominence as its popular, long-serving president, had stepped down just two years earlier. “A benevolent dictator,” Hillemann says. “Faculty were not consulted about much, students not at all. While he was there, the lid stayed on everything.”

To Rodger Poore ’68, the atmosphere was sometimes corny, always collegial. His parents had met at Carleton, but he had never seen the campus until he arrived from California, right before the start of school. He met Harley on the first day of their freshman year—“at a beanie event,” he says. “Jan came over and introduced herself.” Soon they were playing bridge.

Harley was like that, remembers Buser, “the person who could talk to anybody, enjoyed everybody she met, and could drag other people into the friendships she made. She was excited about people, about living.”

When the lid finally did come off, it was gradual, peaceful, and sometimes silly. Already in 1963, students had invented the Reformed Druids of North America to protest Carleton’s religious requirement, arguing that attending their own ceremonies should count. (The requirement ended the following year; the Druids are still around.)

Many students were too preoccupied for protests, druidic or otherwise. “Bookers,” they were called, cloistered in their carrels. “The atmosphere on campus was one of really intense immersion in whatever you were studying,” says Larry Sommer ’68. “You had to work hard. Everyone did.”

Barb Sommer, who was dating Larry at the time, recalls that when the women’s curfew was lifted, the reaction wasn’t anarchy. “More like ‘thank heavens we’re done with that.’ Though maybe my head was in my books.”

By the time men and women were allowed in dorm rooms together—first with three feet on the floor, then without restrictions—the lid was long gone. But even campus graffiti was often more clever than crude. “Oh God, grant me chastity but not yet!” someone scrawled in the tunnel beneath the women’s dorms, a quote from St. Augustine.

To be a Carl in 1967, according to a cheeky compilation of campus slang, was to “arb”—pursuing “bacchanalian rites” in the “spacious arena of natural wonders.” But also to “apple-up” (“become scared, nervous, or tense”) when grades were on the line.

“From 1962 to 1970, the college just transformed immensely,” says Hillemann. And yet, things never got out of hand. Partly because of John Nason, Class of 1926, the courtly Quaker activist who succeeded Gould as president and gave students more of a voice. But also because of what had not changed. “Real smart students, not taking themselves too seriously. A commitment to dialogue. Those have been themes running through Carleton since forever.”

A commitment to service also went way back, to Carleton’s religious roots, though it took on a different flavor in the 1960s. Joe Foran ’71 and Hugh Maynard ’71 helped start the first environmental activism group on campus, after observing a local factory discharging waste into the Cannon River. The administration—overlooking the night that Foran and friends replaced the flag atop the student union with a blackened bedsheet—supported the group and signed off on the school’s first Earth Day celebration, in 1970.

“Certainly there is an irreverence toward authority figures,” Maynard says of the campus culture,

“but also compassion toward those less fortunate.” Hillemann notes the high number of graduates at the time who went into the Peace Corps—Hanna-Davies being one—as well as the State Department and Foreign Service.

“We were all the children of John Kennedy,” says Foran. “Everyone could tell you where they were when news of his assassination came through. His message, of the nobility of public service, reached down to junior high schools. I think an awful lot of us took that to heart.”

Poore was the first of Harley’s friends to go to Washington. After grad school at Harvard, he landed a job in the D.C. area using his physics and math background. Harley arrived soon after, followed by Buser. Eventually, the women moved in with Poore’s neighbor across the hall.

Bridge started up again. Camping, hiking, canoeing. Along with some Carleton-esque capers: car rallies in the countryside, scavenger hunts, a costume party where everyone dressed as vegetables.

At the same time, other Carleton cohorts were arriving in Washington. Foran was recruited right out of school for an internship with the brand-new Environmental Protection Agency. Maynard soon joined him, as a coworker and a roommate. For a time, they shared a house with five other people—all but one were Carls.

Most of these cohorts were unaware of the others, at least at first. “They were like bubbles floating around,” Foran says, “and at some point they would bump into each other and get bigger.” There were so many Carls in D.C., Foran says, that he would often go to meetings on Capitol Hill and notice something familiar about the person across the table.

“Did you go to Carleton?” he’d ask. More often than not, they did.

“Washington is where the action was,” says William Zeisel, a historian of the city. “Before the internet, if you lived anywhere in the country and had a cause and wanted to make it national, you went to Washington. You had to make your presentation. Highly motivated young people of all persuasions were in D.C.”

Buser, an English major, went to work in prison education. (In time, she would become the director of Maryland’s correctional education program.) Harley, a sociology and anthropology major, got a job in the relatively new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, developing Title IX protections for women and girls. “I am quite certain,” Buser says, “that regulations for Title IX were written in our living room in Arlington. People from her office would be there talking late into the night. How can we do this? How can we make this work?”

Harley got the diagnosis in the spring of 1974: breast cancer. Her friends found out soon after. Birthdays had always been “perfectly crazy” occasions for the group, Buser says, and Harley’s was coming up. A plan was hatched.

It fell to Buser to wrangle the park permit, given the gravitas of her work in law enforcement. She walked into the National Park Service headquarters and said, “I need a permit. We’re going to have breakfast on the Mall with champagne.” No one knew what to think. Finally, she was sent upstairs to the head of the park service, who seemed concerned about drunken radicals until he heard about the string quartet. He signed the permit himself.

Buser asked Harley’s mom to send the prom dress. The men rented their outfits. The table was set with a white cloth and candelabras. “It was a really Carleton thing to do,” says Barb Sommer, who was in Duluth, beginning a career as an oral historian, and couldn’t attend. “It was innovative, there were no boundaries, and it was also thoughtful and caring. The problem was posed and the answer was amazing.”

Harley would keep fighting the cancer for years, her friends taking turns driving her to appointments. She would keep traveling, too. Visiting the Sommers in Duluth. Canoeing through the Boundary Waters. She married her boyfriend, Wesley, a couple years after the party.

She also kept working. Toward the end, she would nap in the afternoon and work at night. She did this until just a couple weeks before her death, in the spring of 1982, at 35.

When the photograph of the breakfast was published, that summer of 1974, much of the country would see it as a respite, a light at the end of a tunnel. Nixon would resign three weeks later. The war in Vietnam would end in less than a year.

Photo courtesy of Carleton Archives

“If you go back to 1974, it was a time that seemed to promise everything, even if it might not happen,” Zeisel says. “It made sense that you could have breakfast on the Mall. Why shouldn’t you?”

For Harley and her friends, of course, it was also bittersweet. A few years later, the Post staged an exhibition of its most popular photographs, and several of the friends went and sat beneath the image of themselves, as if to show they were real. But life went on as usual, for the most part, until it didn’t.

The reunion last summer came together at the suggestion of the Post photographer’s daughter, Joyce Naltchayan Boghosian, who had always been intrigued by the image. A table was placed in more or less the same spot. It was set, once again, with 12 chairs. But only six were filled.

Much has changed. Foran notes that many of the agencies where Carls worked in Washington are being dismantled, one way or another. “One of the values imbued by Carleton at the time was tolerance,” he says, “the idea that you don’t know everything. Be curious, not judgmental. That’s something I find myself thinking about now.”

After Harley died, her colleagues in the civil rights office of what is now the Department of Health and Human Services planted a tree in her memory, right on the Mall. It is still there. “She was just an amazing person,” says Buser. “She sought to make the world better for all of those people she drew to her—really, everybody.”

Tim Gihring is a former editor of Minnesota Monthly magazine and the current writer and host of The Object podcast from the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Jack Molloy is an artist based in Naples, Fla.