For many Carls, mid-career shifts are more evolutionary than revolutionary

For Britt Weber ’94, it was the feeling that work had gone stale for her. For Pat Sukhum ’96, it was an unexpected invitation from an executive search firm. For Richard Allen Greene ’91, it was the realization that he’d spent many pandemic lockdown hours reading books by rabbis.

For these Carls, these were the moments when they realized that they were going to make major changes of direction in their careers.

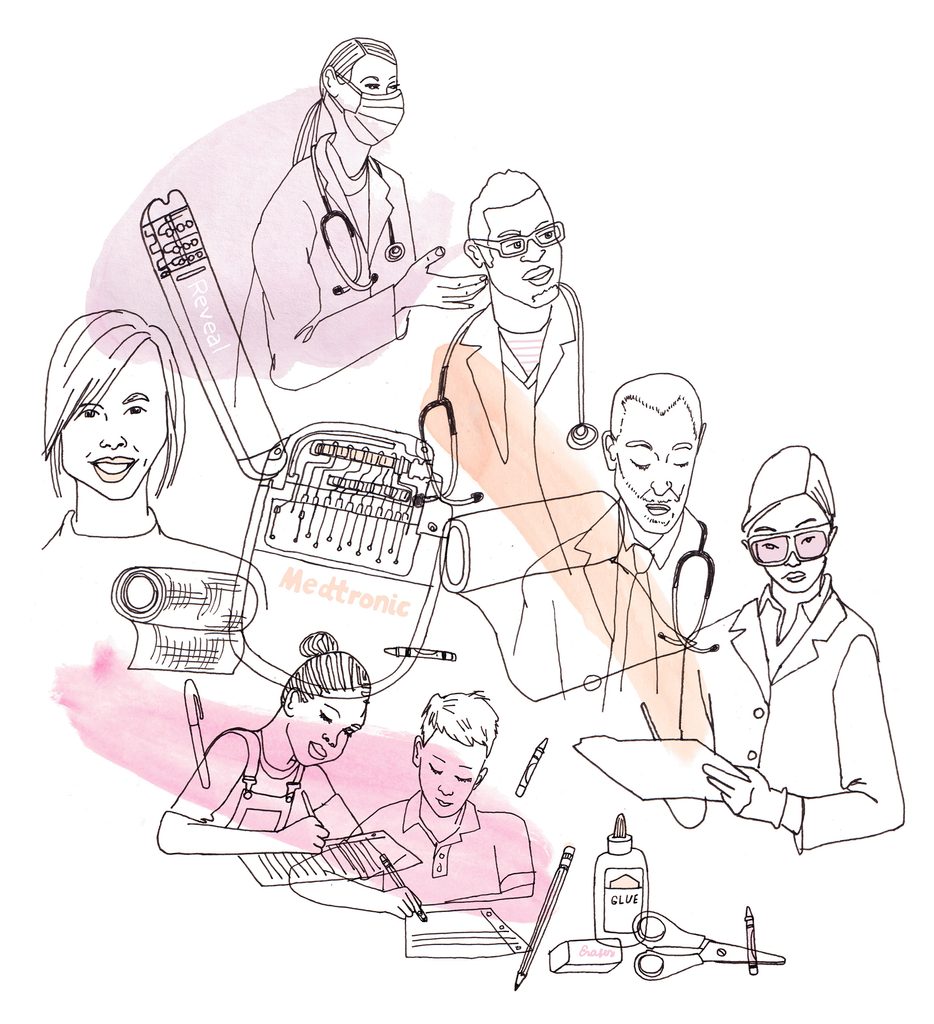

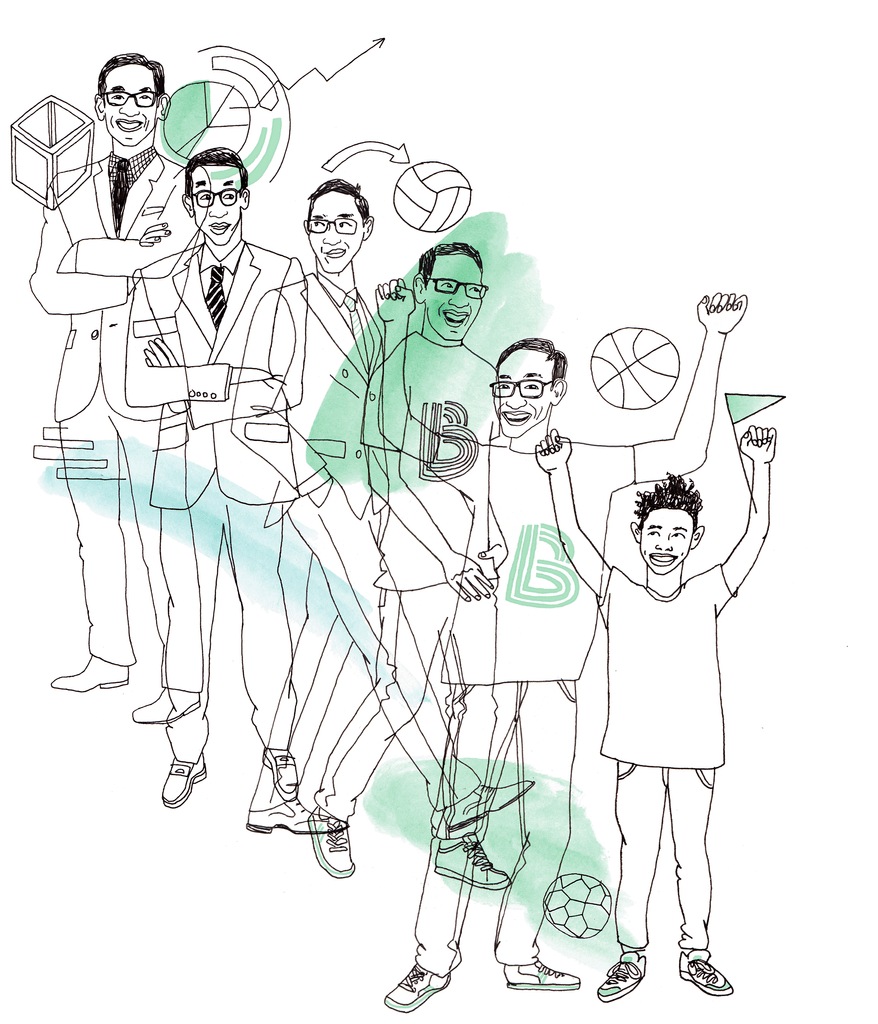

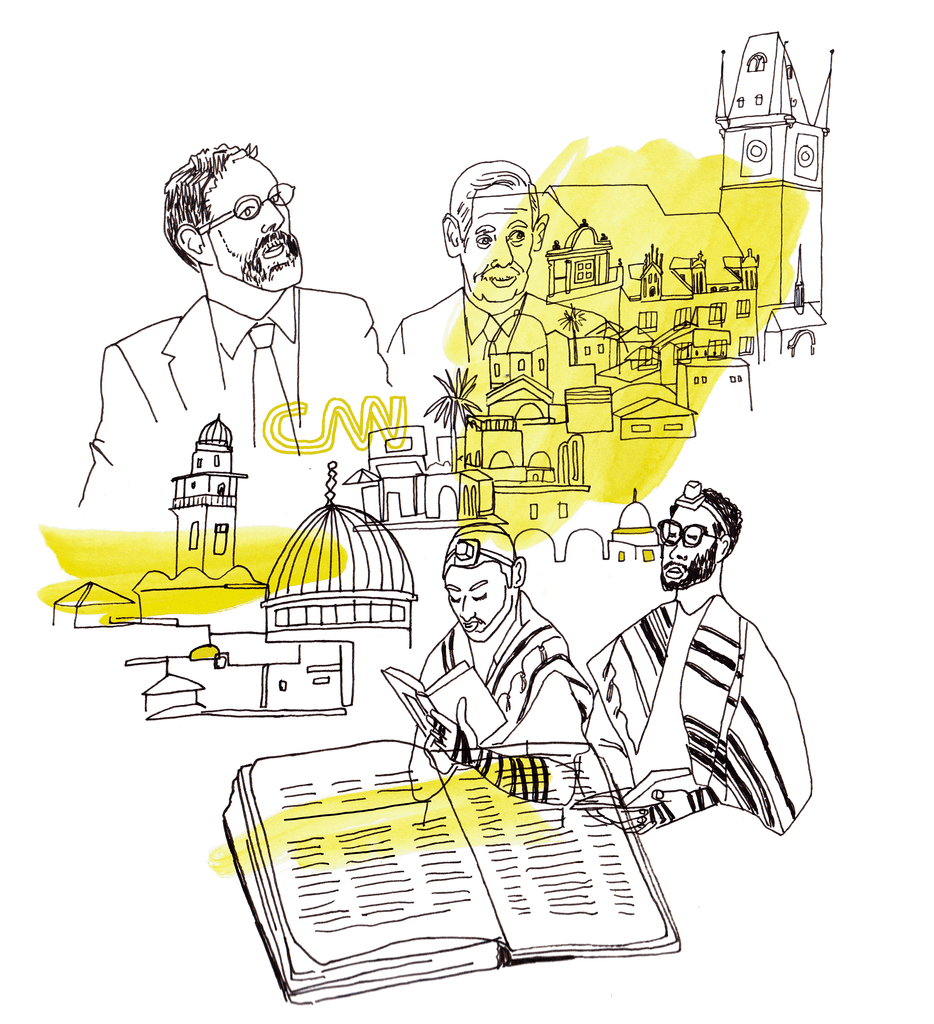

Weber pivoted from full-time work as a medical-device marketer to part-time substitute teaching and paraprofessional work in elementary schools. Sukhum walked away from a successful career as a tech entrepreneur to become the CEO of a youth-development nonprofit. And Greene left a high position at a major news organization to begin five years of study for the rabbinate. While all three retain clear memories of these pivotal events, they also point out that there was a lot more involved in their decisions to change course than the “aha” moments. They paint a complex picture of what it means to make such a shift—a picture that upends simplistic ideas of the “midlife crisis.”

There were early hints of a calling that they didn’t heed; elements in their personalities that craved a different mode of expression; experiences at Carleton that set them up to think flexibly about their futures; activities outside of work that pointed toward the new path. The big changes they made were more evolutionary than revolutionary, involving gradual acquaintance with the possibilities of the new life, mentorship along the way, preparations both psychological and economic, and more.

And yet the changes also brought real discontinuities and challenges as these professionals accustomed to the mindsets, rituals, and values of one sphere were called upon to function in an entirely different one. Some of their attitudes and skills carried over; others had to be abandoned or retooled. The new life brought a pretty steep learning curve.

The Push and Pull of Career Pivots

Michael Wenderoth ’93 is an executive coach and author who regularly works with people considering the kind of career shift that Weber, Sukhum, and Greene made. He sees their situations and their decisions in terms of push and pull.

“I think of the push element as, they’re not happy enough where they are,” he says. “They feel that their job doesn’t have enough meaning for them, or that they can’t make the impact they want to make. There could be some very practical reasons, too; like the position isn’t working out financially for them. On the pull side, it’s all about another opportunity that’s more attractive because it’s more meaningful.”

He says that the search for greater meaning is the most common motivator for a radical change in career paths, especially among his clients in their 40s and 50s, who are often more financially secure than younger workers and can afford to take a pay cut.

Laura Hartpence echoes Wenderoth’s point about the search for meaning and authenticity. She and her colleagues at Carleton’s Career Center not only advise students on career options, but they do their best to keep tabs on grads and their post-college career pathways. “Our mid-career professionals typically have a lot of life experience to draw from, so they’ve continued to learn about themselves and their preferences in the world of work,” she says. “They understand their values and priorities much better as they get to midlife, and they probably feel more confident authentically leaning into what is a good fit for them and worrying less about what other people think about that choice.”

Still, the shift brings insecurities of a different sort. “Americans tend to connect their identity so closely with their work,” Wenderoth says. “Especially if you pivot off the mainstream into a lower-paying position, you might hear an internal voice of judgment—what are my peers going to think of me? And there’s a risk involved. You go from the known to the unknown. I may not love the known, but I know it!”

The stories of our three career-shifting Carls demonstrate how the push and pull factors operated together—somewhat like yin and yang—and illuminate the ways that they dealt with the identity issue, reduced some of the unknowns in their new lives, and faced up to the others.

When the Freshness Is Gone

Britt Weber’s first job was with a group of industrial organizational psychologists, doing human resources consulting. When the group hired a marketing firm for a rebrand, she found herself intrigued by what they did and ended up getting an MBA in marketing.

She landed a job at 3M, ultimately working in the medical division marketing wound dressings. “I liked it, but I was pretty far away from the customer,” she says. “I spent more time with the purchasing people than with doctors or nurses.” So when an opportunity opened up at Medtronic, she jumped at the chance to deal directly with physicians. It was much more satisfying for Weber, but after a decade doing it, she wanted more time with her kids, so she left Medtronic and found part-time work as a marketing consultant with Abbott Labs.

It was while she was consulting that she decided to follow up on an interest in education—she’d taken a couple of ed classes at Carleton—by volunteering in a close friend’s third-grade classroom. “I would go in for four hours every Thursday,” she says, “and work with the kids on math or reading or whatever they needed.”

The day came when she felt that, despite her deep respect for the industry, medical marketing “just wasn’t new and fresh for me anymore.” The friend in whose classroom she’d volunteered told her that the need for substitute teachers was dire, and the job didn’t require a teaching certificate. So Weber signed on with the company that handles substitute teachers in Minnesota.

The first assignment she volunteered for, in January of 2024, was a rugged eye-opener. “It was a ‘high-needs resource room,’ and all the kids were on the autism spectrum, and nonverbal. They communicated by pressing different computer icons. One boy would get so frustrated that he would lash out, hit, and yank the lanyard I wore around my neck.”

The experience didn’t deter Weber; she continues to substitute in both mainstream and special education classes, sometimes as a teacher, sometimes in the paraprofessional role, where she interacts with a few students with particular needs—encouraging them, helping them get started on projects, keeping them focused. “I’m a teacher’s helper,” she says.

To counteract what she considers the biggest drawback of subbing, coming in “cold” to a school where you’re unknown and you don’t know anyone, she learned to stay with a single school. And she’s drawn upon the advice of the friend who got her interested in subbing in the first place. “She has been a mentor,” Weber says. “If I hadn’t had her, I don’t think it would have gone as well as it has.”

And as for the kids, “I just really like being around them. They’re so honest. Often, I’ll get a few hugs on my way out the door at the end of the day, which I love. And I love being a positive influence in their lives, giving kids good feedback and encouraging them.”

Asked if she misses marketing, her answer is succinct.

“No.”

A Perspective Shift

When a recruiter from the business-management consultancy Deloitte came to Carleton, Pat Sukhum decided it was the company for him.

“I got my first suit, my first credit card. I was pretending to be a grownup,” he recalls with a smile. “When you get there, Deloitte assigns you. And I got assigned to healthcare projects. I could have gotten retail or telecom, but I got healthcare.”

It was a fateful assignment. After a couple of years with the company, Sukhum and a colleague left Deloitte and joined up with other young entrepreneurs to create what many others were creating in the dot-com boom years: tech startups.

“We were in this environment with people who were just really brilliant, with a lot of great ideas,” he says. “Healthcare represented opportunity, because a lot of healthcare was broken.”

That realization would lead Sukhum to cofound three startups: Definity Health, the first to bring the healthcare savings account concept to market; RedBrick Health, which promoted wellness and population health; and Bind, later Surest, a healthcare plan emphasizing cost transparency.

But another fabric was being woven into his life too. “The same week I left Deloitte to go to Definity, I was sitting at Deloitte and there was a phone book on the desk,” he says. “I opened it, called Big Brothers Big Sisters and said, ‘Hey, I want to be a Big Brother.’ I don’t remember if I had seen a BBBS presentation or a billboard—it was just on my mind.”

Volunteering to mentor a boy in the venerable youth-development nonprofit put Derrick Pam, then nine, in Sukhum’s life. “That meeting changed who I am, my compassion, my perspective,” he says. “The world became bigger for me.”

As he spent time with Derrick, he also began to volunteer at the Twin Cities BBBS, eventually joining its board in 2010. Ten years later, the organization was in search of a new CEO, and the board sent Sukhum to the search firm they’d employed, to help them write the job description.

“At the end of my conversation with the headhunters, they said, ‘have you ever thought about applying?’ Well, I’m a health-tech startup guy, right? It just wasn’t in my head.” He was tempted—but hesitant. It was Derrick Pam who finally persuaded him to apply. He was hired in 2021.

“I loved the tech startup world,” he says. “Fast pace, high accountability, lots of execution. But here at BBBS, it’s all about relationships, empathy, kindness. That’s what we hire for. I have to balance execution and accountability, which we need to keep us solvent, with empathy and relationships and kindness, which is so important in an organization to which parents entrust their kids.” He’s had to be gently reminded from time to time, he says, to keep that balance from tipping over into too much emphasis on the bottom line. “It’s probably the hardest job I’ve ever had,” he says, “but it does feel more genuine to who I am. I’ve always valued relationships, and outside of work, I’ve always been loose, fun, and social.”

And as for the boy, now a man, who changed Sukhum’s perspective, “we really became brothers,” Sukhum says. “Derrick was the best man at our wedding. Our families are intertwined. I think meeting him was the best decision I’ve ever made.”

Answering a Recurring Question

What persuades a veteran journalist high up on the org chart at CNN to leave and spend five years studying Hebrew, Aramaic, and the intricacies of the Talmud, the vast set of writings that’s the main source of Jewish law and theology?

For Richard Allen Greene, it was the realization that part of him had wanted to be a rabbi since Carleton days.

“When I was a junior, I had a conversation with my rabbi about it,” he says. “I’d been active in Jewish groups at Carleton, and Reynolds House. I was invited to the Hebrew Union College’s Spring Colloquium on Jewish topics, in New York, and enjoyed it. But I didn’t follow up. Life happened. I graduated, went abroad. I got a girlfriend whom I ended up marrying. I started a career that I enjoyed very much in journalism.”

That career began with Greene taking off to Prague, a popular destination for young Americans in the ’90s, to teach English. He ended up as a reporter for the Prague Post, the city’s new English-language newspaper. Working for the BBC in London and the U.S., and then for CNN, he traveled to the Middle East with Czech President Václav Havel and covered Hurricane Katrina, the election of Pope Francis, the Oscar Pistorius murder trial in South Africa, and many other major stories. He became director of content at CNN London and then the network’s Jerusalem bureau chief.

“But about every 10 years or so,” he says, “my brain would say, ‘What about becoming a rabbi?’ I would go and talk to whoever my rabbi was at the time.” During one such conversation, his rabbi encouraged him to take one of the lay-leadership courses run by Liberal Judaism, one of the two Jewish organizations in the U.K. that correspond to Reform Judaism in the U.S. After that, he began leading occasional services in small Jewish communities around Britain.

But it was the COVID-19 lockdown that persuaded him to take the next step.

“I couldn’t go to the gym before work in the morning,” he says. “So I sat in the kitchen and read books by rabbis, books that had sat unread on my bedside table for years. I took an online course in the Talmud. When we got to the end of the year, I thought, what did I do with my free time? I read books by rabbis and studied the Talmud. It’s finally time to give in.”

At the end of 2020, he applied to study at the Leo Baeck College in London, the U.K.’s school for rabbis in the liberal, or progressive, tradition, and was accepted. A four-year process of preparation ensued, during which Greene relocated to Jerusalem to head CNN’s bureau there during Hamas’s attack on Israel and the Israeli strikes on Gaza. Meanwhile, the family prepared for Greene’s upcoming five-year period of study, during which he would draw no salary. By June 2024, he was back in London—“getting on my bicycle and riding to school in the morning,” he says.

He studies the Talmud, Biblical Hebrew, and Aramaic—the close relative of Hebrew in which the Babylonian Talmud is written—along with counseling skills, Jewish history, and many other topics. His background in journalism gives him perspectives on the many real-world issues that come up in Jewish law, he believes—and when it comes to writing papers for his classes, “I’m not intimidated, and I write fast.”

But here’s how he describes what is perhaps the strongest legacy he carries over from journalism into a profession, and a religious world, in which study is akin to prayer: “There’s a quote attributed to G. K. Chesterton, which I have not been able to verify,” he says. ‘A journalist is a person who educates himself in public.’ I can leave Carleton, I can leave journalism, but nothing can make me stop studying.”

Jon Spayde writes about education, psychology, medical issues, art, and craft for a number of Twin Cities and national publications.

Julia Rothman is an illustrator and author. Her book Insect Anatomy comes out this fall.